Breaking it Down: What Is Fibrin?

As a child, how many times did you get a cut, a scrape or some other minor injury that caused you to form a scab? How many times did you look at that scab and wonder just what it was? Well, among other things, that scab was–and is–now fibrin. Fibrin is a complex polymer created by your body to form clots and scabs.

From the name alone, we get the idea that fibrin might have some sort of fabric-like qualities. And that’s a great place to start thinking about it. Fibrin is one of the important parts in how our bodies trigger coagulation, clotting and how we maintain hemostasis, the keeping of our blood inside our bodies.

In brief, fibrin starts out as fibrinogen in our blood. Fibrinogen is a plasma-soluble protein. Via complex, enzyme-based reactions called the Extrinsic Pathway (damage to our tissues or veins) or the Intrinsic Pathway (caused by infection or inflammation), fibrinogen will arrange itself into a series of strands (called polymerization) that eventually progress into what we recognize as a blood clot.

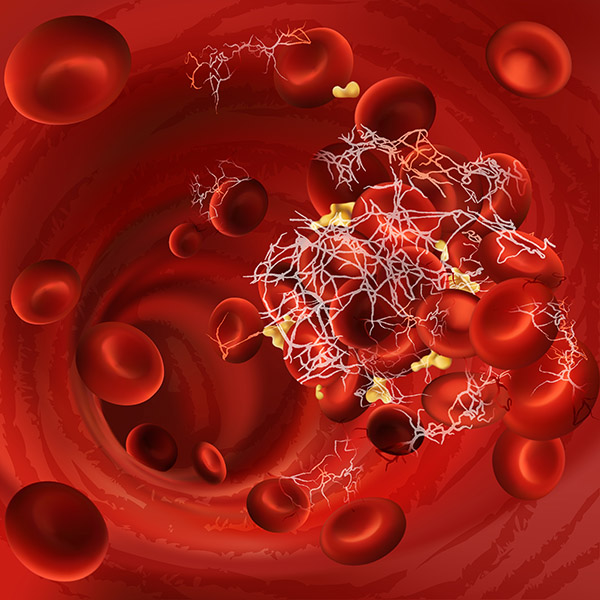

As we have all had occasion to suffer injuries, we have certainly seen scabs and clotted blood on our own bodies. If you’ve ever been curious enough to look closely at those scabs, you’ve likely seen what looks like thin little white fibers coming out from the body of the scab itself. Those little white fiber-like structures are what fibrin looks like on a macroscopic level.

If you were to take the time to look at that material under a microscope, you’d find yourself looking at a very porous, almost spider web-looking structure. That is what fibrin looks like on a microscopic level.

Unfortunately, whereas fibrin plays a very important role in the process of healing wounds and tissue damage, as we age, changes can and do occur. These changes include coagulation and fibrinolytic factors. Research demonstrates that healthy, aged individuals have heightened coagulation enzyme activity, accompanied by enhanced formation of fibrin and secondary hyperfibrinolysis. The result is a greater risk for various types of thrombosis, a venous or arterial blood clot. A thrombosis is the result of an overproduction of fibrin. Not only is it detrimental to health, but can be life-threatening. An example of one we all know is a stroke–a blood clot in the brain that can leave a person disabled or worse.

There are other forms of thrombosis we hear about. It is often stressed in our sedentary lives how important it is to get up and move around every few hours. The reason that is so important is to avoid the development of blood clots in our legs, or Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT). These blood clots can move through the circulatory system and into the lungs, heart or brain, and can be fatal. Another type is pulmonary embolism (PE), a blockage of one of the pulmonary arteries. The greatest danger of a PE clot occurs more common post-surgically. It is typically treated preventatively with low dose heparin, an important anticoagulant.

In addition to DVT and PE blood clots, there are a number of conditions and syndromes that arise from the lack of production, or improper production, of the chemicals responsible for triggering the change from fibrinogen into fibrin. Genetic disorders and liver damage (be it from disease or environmental factors) are the more common causes of such issues that are collectively recognized as hemophilia.

In addition to DVT and PE blood clots, there are a number of conditions and syndromes that arise from the lack of production, or improper production, of the chemicals responsible for triggering the change from fibrinogen into fibrin. Genetic disorders and liver damage (be it from disease or environmental factors) are the more common causes of such issues that are collectively recognized as hemophilia.

But as complex and dangerous as both the overproduction and the improper or lessened production of fibrin can be, medicine has also found some great treatments for these issues. From taking the simple, ubiquitous low dose aspirin once a day to the administration of prescription anticoagulants, like Warfarin, there are numerous ways to treat these disorders in a preemptive, therapeutic setting.

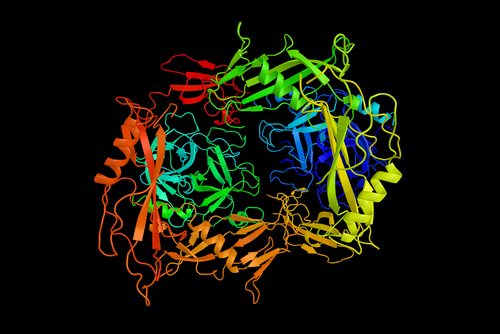

But what do we do in an emergency setting? What happens when a patient arrives at the emergency room with a DVT or PE blood clot? The doctor has several options, but one of the classic standbys is an enzyme called streptokinase. Discovered in the 1930s, streptokinase is a chemical originally produced by strains of bacteria. The bacteria produce streptokinase as a way to isolate and protect itself from the immune system in our bodies. Scientists and doctors have learned how to synthesize the protein and use it as a treatment for thrombosis.

Streptokinase works by triggering the body’s release of plasmin, which breaks down fibrin clots. When administered to a patient suffering from thrombosis, the enzyme’s actions cause the clot to break down in rapid fashion, lessening the effects and severity of a thrombosis.

Streptokinase works by triggering the body’s release of plasmin, which breaks down fibrin clots. When administered to a patient suffering from thrombosis, the enzyme’s actions cause the clot to break down in rapid fashion, lessening the effects and severity of a thrombosis.

Although streptokinase use is no longer as prevalent as it was, other medication that functions in the same manner (triggering the release of plasmin to break down fibrin) is very common. Enzymes like anistreplase and tenecteplase are popular, as are other treatments.

Of course, trips to the emergency room are not common, unless it is for such serious things as strokes and heart attacks. Someone may just want to know how to promote healthy fibrin metabolism. There are options that don’t involve severe conditions.

Fibrin and its importance cannot be overstated. We have all seen fibrin since our earliest childhood injuries, both minor and major. Many of us never gave those old scratches and cuts a second thought. Not only is the substance required for our bodies to heal the damage that is caused in everyday life, but its ineffective production can also cause major health-related concerns and could even be fatal.